Participants

- Eoghan

- Christian Gonzales

- Taylor Kuiken

- Ryan Marshall

- Pierson Miller

- Andrew Orr

- Levi Ramsey

- Cameron Sanchez

- Alex Seaton

- Erin Vair-Grilley

- Minori Yoshida

Friday 12th December

Alex and Minori were the first to arrive at the field house at around 7:30pm, with Cameron arriving just afterwards. We got to work preparing dinner (fettuccine with Alfredo sauce), along with the meal for Saturday (Irish stew).

We were soon joined by Andrew, Christian, Pierson, Ryan, Levi, and Taylor, who were quickly roped in to helping out.

Since we had four new participants, we took a moment after dinner to introduce them to the project and explain our goals. Erin and Eoghan showed up soon after, and with everyone present, we discussed the options for the next day. We had 11 people, so we decided to split into four teams, with three teams of three, and a team of two. The team assignments were:

- Andrew & Eoghan: Ridgewalking near Sparks-Zalea

- Erin, Taylor, and Cameron: survey in Tummy Troubles

- Minori, Christian, and Pierson: survey in Wedgie cave

- Alex, Ryan, and Levi: ridgewalking and some exploratory digs south of 3-BJD.

By this point it was past midnight(!), so we headed to bed to get a few hours of sleep.

Saturday 13th December

Saturday began with blazing sun and blue skies. Perfect weather conditions for a day out in the field! After the customary safety briefing at 8am, the various teams headed out towards the caves.

Ridgewalking team

Andrew Orr (TL), Eoghan

The primary objective for our team was ridgewalking. After discussing potential work areas the previous night with Alex, we decided to focus on a region north of County Road B024 and west of County Road B020. Within this area, there were roughly 15 points of interest (POIs) requiring investigation.

Saturday morning brought bright, clear skies with temperatures hovering around 35–40°F. A brisk wind of approximately 10 mph made it feel even cooler. We parked the car, prepared our hiking gear, and planned to switch into caving equipment once we located a promising cave.

Our first POI proved to not be a cave and we updated our records to reflect “no cave.” After adding a few more “no cave” entries in QField, Eoghan continued logging points while Andrew scouted for other potential sites. He soon identified a spot that showed some promise. We donned minimal caving gear and entered an opening just a few feet wide that extended back about five feet. From there, it dropped into a small pit roughly 20 feet deep.

Andrew took a quick look at the pit before backing out to coordinate, while Eoghan proceeded to assess the descent. He determined it was feasible to climb down using ledges and rocks for footholds and handholds. Near the bottom, Eoghan discovered a hibernating bat, and we agreed to leave it undisturbed. We concluded this cave warrants a return visit in the spring, once bats are no longer hibernating, to determine if there is a passageway beyond the pit.

Following this exploration, we continued checking POIs until noon but found no additional promising leads. We returned to the car for a quick lunch out of the wind. Afterward, we had few remaining POIs in the immediate area, so we opted to drive to another location. From there, we walked about 1.5 miles to access POIs on BLM land. Although the most direct route from the south crossed private property, we were able to reach the points by approaching from the northeast which was BLM land. One spot appeared to have potential as a dig, though it would require considerable effort. We logged our observations and moved on.

As the day wound down, we discovered that several additional POIs had apparently been investigated previously since we could see GPS tracks going to them, despite being marked as unvisited. After confirming they had been checked, we decided not to revisit them. With daylight fading, we concluded our work for the day and returned to the field house.

Ridgewalking & dig team

Alex Seaton (TL), Ryan Marshall, Levi Ramsey

Our objective for the day was to continue investigating an area that Alex, Riley, Sharon, and Vanessa had previously been ridgewalking.

On our March 2024 trip, Alex and Riley had found two locations where arroyos sink underground, but both were clogged with sediment and other material. There were also a few locations we hadn’t got around to investigating.

For this trip, we planned to try digging both of the plugged sinks and see if we could find a way into the caves that are presumably underneath. If that didn’t go to plan we could also look into the other POIs.

On our way to the parking spot, we stopped at 3-BJD cave to take a look at the entrance as Ryan and Levi hadn’t been there before. The cave was previously explored under GypKaP, but would be worth revisiting at some point. We noted the tricky entrance climb and discussed possible options for rigging a rope.

We also stopped to tidy up our data in QField for a couple of other POIs along the way. After re-investigating these we concluded that neither were caves.

With these quick tasks out of the way, we arrived at the parking spot and geared up for the rest of the day.

Dig No. 1

Next we headed to the first dig, just north of where we parked. On the way, Alex pointed out the large drainage that feeds the sink. The drainage abruptly ends at the base of a hill, with a limestone boulder the size of a small house above the point where the water appears to sink underground.

Underneath the boulder, what is presumably a cave entrance was choked with tumbleweed and plastic buckets. Since the last visit, there had clearly been fresh water flow into the sink, and we noticed several additional plastic buckets that weren’t there in March and must have been washed in over the summer.

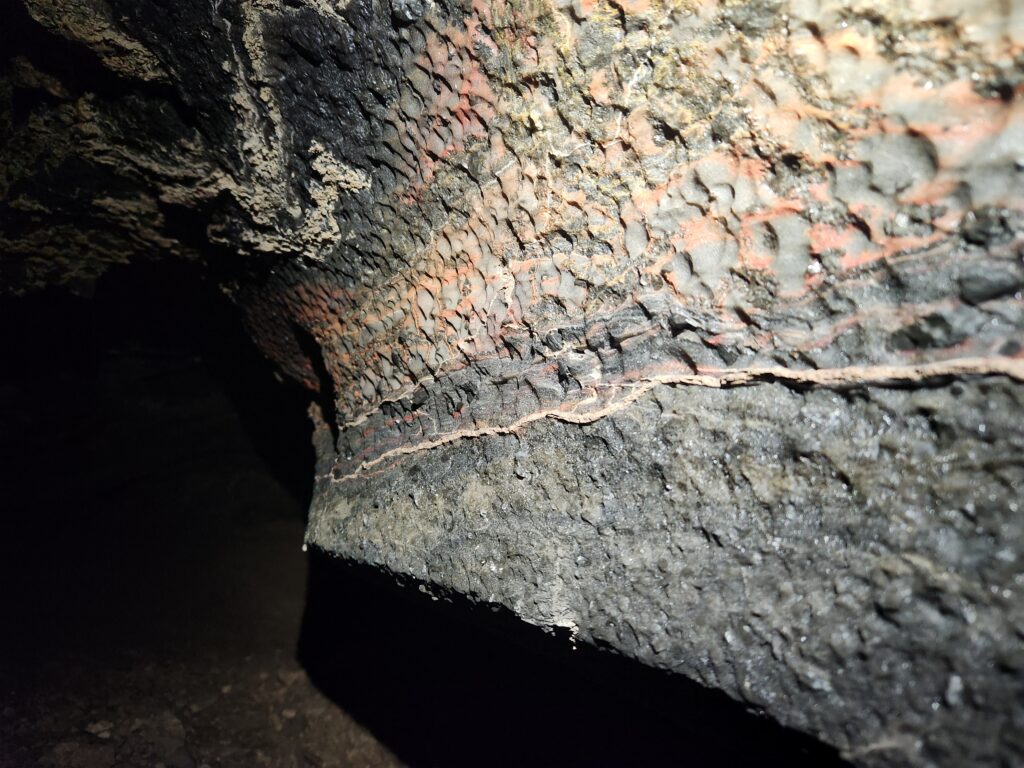

We got to work pulling things out of the choke. We ended up removing a total of eight(!) plastic buckets, along with a bunch of tumbleweed. With this out the way, there was unfortunately no obvious continuation. On the lower side of the sink at the left, there’s a small amount of exposed scalloped gypsum, but no obvious way on. Since the floor in that area is sediment, we figured that digging this might reveal something. Ryan made a heroic effort on this, and exposed what appears to be a very narrow (3-4″) wide gypsum canyon passage, but this is currently far too small to be entered.

We took a break to consider our options. While the sink clearly takes a decent amount of water, it seemed that the work we’d need to do to get access to whatever cave is underneath would be pretty significant. We hadn’t set out to take on such a big job, and only had permission from the BLM for a relatively small exploratory dig, so we figured we’d shelve this project and perhaps come back to it some other time.

Dig No. 2

Our next stop was another sink further east. This also has a pretty substantial drainage area feeding it. The water sinks at the base of a small, roughly 15ft tall gypsum cliff. At the top of the cliff, there’s a roughly 10ft wide, 15ft deep pit, at the bottom of which the passage entering from the sink can be seen. In other words, the passage from the sink goes about 6ft before emerging at the base of the pit. On our previous visit in March, Riley and Alex had noted a possible continuation on the far side of the pit, and found the passage from the sink to the pit was choked with sediment.

Unfortunately, we had no way of entering the pit from above, so our only way to get to the lead was to dig the sediment out of the passage from the sink to the pit.

This turned out to be pretty tedious! We each took it in turns to work on pulling out sediment. The entrance had an awkward dip 2-3ft deep, which made it hard to access, and we were somewhat limited with the tools we had; a larger shovel would have helped quite a bit. On the plus side, the plastic bucket that had been stuck in the entrance came in handy for shifting sediment out of the dig.

After several attempts each at working at it (admittedly with Ryan doing the lion’s share of the work), and about two hours, Ryan attempted to squeeze through. While he was able to get most of his torso into the pit, he couldn’t get his legs through since he would have had to bend them the wrong way. To make matters worse, in attempting the squeeze he’d pushed sediment back into the dig, so ended up stuck for around five minutes while Levi dug it back out.

Eyeing this up, Alex figured he might be able to make it through. After moving one rock that had been jabbing Ryan in the back, Alex was able to get through. He was then able to pull out the various small rocks that were constricting the squeeze, and after about five minutes work Ryan was able to fit through easily.

We next inspected the main lead on the far side of the pit. This was choked with large rocks, another plastic bucket, and some vegetation that had been washed in. Fortunately, this was much easier to shift than the sediment we had previously been digging, and so after a few more minutes work we uncovered a cave entrance. It was a relief that we hadn’t just spent two hours digging for nothing!

After opening up the entrance, Ryan poked his head inside to take a look. The passage is pretty tight, and appears to go around 10-15ft to what appears to be a drop.

Ryan was just about to proceed into the cave, when he noticed a snake skin part way along the passage. Considering how many snakes he’d seen recently, and how warm the weather was, he opted to retreat and give this a try some other day. It was also getting to the end of the day anyway, so this was a good time to stop.

We made our way out through the dig and tidied up before heading back to the vehicles. Hopefully this lead will be explored soon!

Wedgie cave survey

Minori Yoshida (TL), Christian Gonzales, Pierson Miller

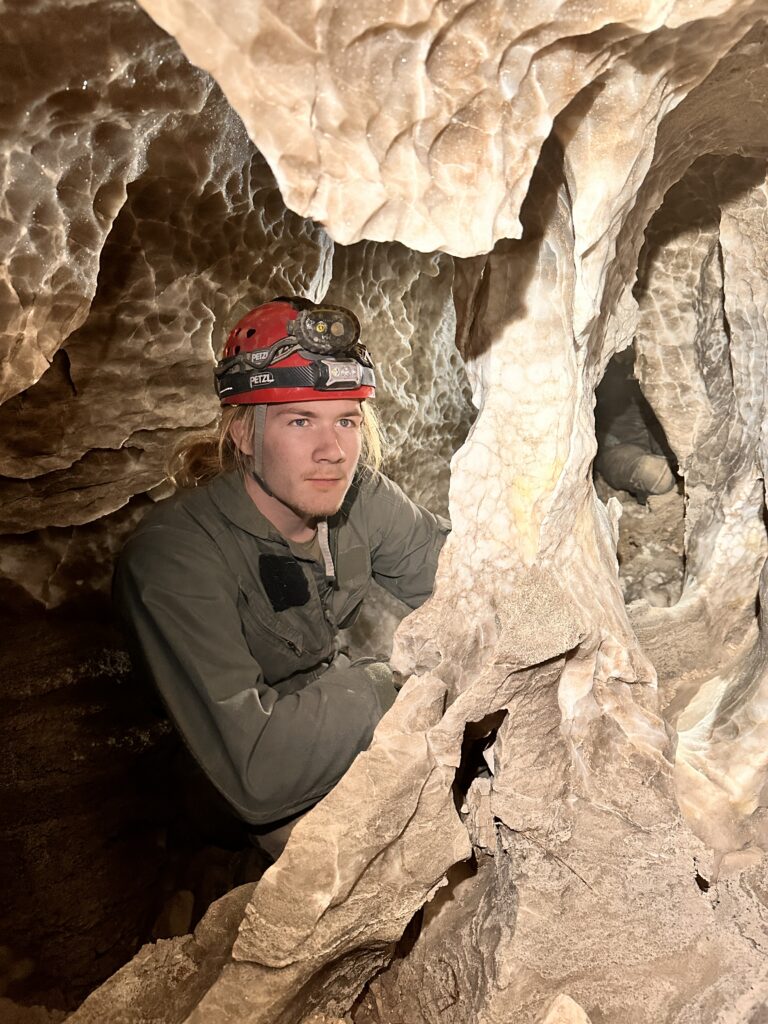

It was a nice warm and sunny day, it was almost a shame not to be ridgewalking. Pierson repaired his boots with generous amounts of duct tape. The team geared up and got to the entrance around 10:30 am. Pierson and Christian worked in front of Minori to locate survey stations that were hard-marked. It was Christian’s 2nd time in a wild cave, and he did well with all the tight crawling and pinchy small passages. Minori worked on the tablet using Topodroid to sketch in walls and features on top of the line-plot that was created on the previous trip. The upper level was sketched on one scrap, and the lower level was another scrap.

We reached the end of the existing line survey at station A29, so Minori taught Christian how to set new stations and hard-mark them on the wall. The team then surveyed beyond what was explored on the previous trip. They carefully manoeuvred beyond a precariously hanging rock lodged in the passage. The stream passage made a few twists and a section had sharp nodules protruding into the passage and had to manoeuvred by crawling under them.

The team got to a point where the passage broke into multiple branches and got slightly mazy. Minori stopped survey here at station A51 and the team explored the section for about 15 minutes. They turned back around 3:30 pm and exited around 4:30 pm. Two bats were observed in the cave, at A15 and A23. Minori realized she lost the stylus to the tablet somewhere on the way out; hopefully it can be retrieved on the next trip. Additional trips will be needed to fully explore and survey a side lead, and the passage where the team stopped.

Tummy Troubles survey

Erin Vair-Grilley (TL), Taylor Kuiken, Cameron Sanchez

Our team’s goal was to line survey as far as possible, continuing from the last set survey station. The three of us set off to the cave entrance. The weather was warm for December, and sunny, predicted to stay the same throughout the day.

This was Taylor’s first time in a wild cave, so we were hoping that good progress would be made and neat cave passage would be seen. We set off towards the last set survey marker which was A46. The route to A46 is straightforward, however, it requires a lot of crawling on sharp, stabby rocks. (This is a foreshadowing for the rest of the day.) We got to A46 quickly and without any noteworthy comments at around 10:45am. Once there, Taylor and Cameron got a quick briefing on how to set survey stations and the intention behind setting them.

Once the training was over, the line surveying began. Taylor and Cameron set survey stations efficiently and effectively.

Just after A46, the cave passage drops down to a lower level. The lower level is similar to previous sections of the cave in that the floor is rough, sharp rock debris and the ceiling is mostly well formed cave wall. The passageway alternates between hands and knees crawling, belly crawling and the occasional place where you can stand up in a chimney. The dirt was not dry in this level (no dust kicked up when travelling through), but also not damp enough to leave wet patches on one’s clothes.

One thing to note is that somewhere between A46 and A58 the survey markers that we hard marked on the cave versus the survey markers listed in TopoDroid got off by one. Erin tried to go back and determine where we got off, however she was unable to determine where we went wrong in a timely manner. In the interest of time, she simply renumbered the stations in TopoDroid from A59 on. In other words, the survey stations in TopoDroid from A59 to the end of our line survey match the hard marked survey stations in the cave, but somewhere between A46 and A58 the survey and hard marked stations are off by one. We’ll return to the cave in the future to fix the station numbering, though we don’t believe it impacts the line survey.

We eventually got to a cave passage that differed from the previous cave passage. The floor was smooth and there was no sharp, stabby rock debris. The ceiling and walls were still well-formed cave passage. This was a nice reprieve on the knees and hands. Sections of this cave also had a deep trench through the center, so we were able to kind of stoop-walk, even though the floor to the ceiling space was still only crawling height. This section of the cave gave us hope that the cave would continue on as it appeared that water flowed freely and quickly through this section.

We encountered a change in the cave passage around A82 that kind of dashed our hopes of the cave continuing on and on. The passage that was encountered had a height that accommodated belly crawling and was about 10 feet in width. The floor became rocky again, but these rocks were stream smoothed so they were round, and not as sharp and stabby. We proceeded on, our curiosity piqued. Just past this pinch point, the passageway opened up again to hands and knees crawling. The floor was not littered with rock debris and the ceiling and walls were well formed. Shortly after, the cave passage changed again, there was a large room with breakdown. This was by far the largest breakdown encountered thus far.

The most obvious way to proceed was downward. Previously, the cave had a slow downward decent deeper into the earth, hardly noticeable even, but at/after this breakdown room, there were several places where several feet of depth were gained over a series of short horizontal spans. The passageway was primarily through breakdown, but easily passable. Turning another corner, the end was seemingly in sight. The standing passage, shrunk to about 2 feet (generously) in height and proceeded under a breakdown block. I crawled under, hoping the cave continued. Much to our dismay, the way forward pinched out. There was a fin of rock that hindered forward progression although one could see at least a bit more passage further ahead. Another small hole to the left pinched out in breakdown too. Not accepting defeat we poked around in the breakdown room/breakdown passageway in the hope of finding something that proceeded. No luck. We did note though that the breakdown was very unstable. Particularly unstable as you climbed up into the void that it created in the ceiling. There was organic matter high up on the walls down towards the end of the cave, which may suggest that the water level gets quite high as it drains slowly away.

After exploring the breakdown room, convinced there wasn’t a passable way on, we line surveyed down into the passageway described above, setting station A90 and a terminus station.

There was discussion later that night about the potential to revisit the “end” and reevaluate with fresh eyes.

The last stations were set, so the three of us headed out of the cave. We were very nearly at our turn-around time anyway, our goals accomplished with about 20 minutes to spare. Good time out of the cave was made, it took about an hour and ten minutes from the end of the cave to get to the surface with minimal breaks. Our knees, shins, elbows, forearms and hands were well abused and we were ready to be off them and back on our feet (for more than a few steps!).

No bats were seen, and no new mold patches observed (in a previous trip there were patches of white mold on the floor, they were still present but unchanged visibly). A few pieces of glass were found towards the end of the cave, but compared to other caves in the area the cave remains largely trash free.

We exited the cave in evening light. A great day was had by all!

Sunday 14th December

DistoX calibration – Fenced Off Pit

Alex Seaton (TL), Pierson Miller, Andrew Orr, Erin Vair-Grilley

Since we were having issues with Topodroid flagging up shots as unreliable from some of the DistoXs, we figured they were in need of calibration. Doing a training session at Fenced Off Pit was a good opportunity to take care of this, teach people how to calibrate the DistoXs, and also do some SRT practice in a fun cave.

After driving out to the cave and parking by the entrance we got changed and started setting the rigging up, this time with Erin’s Subaru as the anchor. The weather was generally good, but it was very windy, so we were keen to get underground.

Alex descended first, and did some rock gardening on the way down. The others followed soon after.

At the bottom of the first pitch, we found a small bat under a ledge. Trying our best not to disturb it, we headed on down the second pitch.

After dropping this, we regrouped in the main chamber of the cave. This is a nice big space, and was a perfect spot for us to practice calibrating the distos.

Alex handed out a disto and tablet each to Pierson, Andrew, and Erin, and explained the basics of how the calibration process works. They then got to work on putting this into practice. We only had an hour before we had to head back out, which meant that we needed to work quickly.

The calibration procedure is tedious, and there’s a steep learning curve to Topodroid. Despite this, everyone did a great job and by the time we had to stop, we had two of the three DistoXs calibrated.

With our main objective completed, we headed back out to the surface. It was a fun trip!

Ridgewalking

Minori Yoshida (TL), Taylor Kuiken, Cameron Sanchez

The team decided to check out some POIs near Sparks-Zalea cave. They did not look very promising but were clustered close enough that they could be checked out quickly.

Taylor pointed out an interesting feature seen from the road. By the time the team parked and walked out to the feature, the QField satellite data updated and the team realized that the feature was the Zalea entrance.

The other POIs nearby were shallow depressions or collapses with no cave entrances. There were several labeled “trash pits” but the points were inaccurate. One of the trash pits was a site that was cleaned up a few years ago. There are still small pieces of trash but there is no obvious cave entrance. Nearby is another small trash dump, filled mostly with old wood and rusty wire.

Cave marker installation

Eoghan (TL), Ryan Marshall, Levi Ramsey

Our task for the day was to tag three caves (Alien Crash Cave, Wedgie cave, and Sidewinder cave). Ryan drove us out and we hit Alien Crash Cave first, so named for the famous Roswell crash site. Eoghan had done a few of these tags already so this wasn’t anything new. But as usual the issue was finding a suitable place to put the marker so that it is visible but out of the weather. That of course is not such a problem with limestone, but with gypsum it’s a different ball game. Having found a suitable spot at Alien Crash cave we each took a task, i.e. drilling the hole, pumping in the glue, or tapping the marker in.

We next headed over to Wedgie cave, and had a much harder time finding something solid to put the marker in. In the end we opted for a block of gypsum that is probably 400 or 500 pounds, or just slightly lighter than a 5.7L Chrysler Hemi. Then two things happened: we split the piece of wood used to tap the markers into place (it was already on its last legs with a big split down it), and finally we noticed that the block of gypsum had some cracks caused by the hammer blows (hopefully the Loctite takes care of that).

Finally, we walked over to Sidewinder cave, where we found a nice spot to pop in the marker. By this time, the splinters of wood were too far gone to be much use for hammering the marker in. Thankfully Levi offered up his hat to use as a cushion between the hammer and the marker, though unfortunately Levi’s hat melted from the hammer blows. On our return to the truck, we found a small shelter cave near a large depression. In theory it could be dug to go a bit further, though not much passage was visible. Ryan’s analysis was that it looked like the tick infested cave that we found in October. We intended on going to hit another couple of POIs but were hampered by fences and our time constraints.