Participants

- Jesse Adamczyk

- Evan Bowen

- Eoghan

- Ethan Haft

- Sarah Haft

- Ryan Marshall

- Austin McCrary

- Pierson Miller

- Andrew Orr

- Carrin

- Cameron Sanchez

- Alex Seaton

- Erin Vair-Grilley

Friday 7th March

On reaching the field house in the evening, we got to work preparing dinner for the weekend. This time the menu was a creamy shrimp and pasta recipe for Friday, while Saturday’s meal was a slow cooked chicken curry.

After dinner and meal preparation, we organised the teams for Saturday. We had thirteen people in total, so arranged the group into four teams.

Saturday 8th March

Wedgie cave survey

Erin Vair-Grilley (TL), Eoghan, Sarah Haft

Saturday morning was cold and snow flurries were coming and going. There were small bouts of sun, but not enough to warm the morning.

We loaded the car for a survey trip to wrap things up in Wedgie cave. This was getting a reputation for being tight and miserable, so the three of us were in for some sort of treat. This was Sarah’s first cave, although not her first time underground; Eoghan hadn’t visited Wedgie cave; and Erin had previously made it to station A20, but no further. The tasks at hand were to go to survey the end of the cave and mop up what remained, poke around in some left-over leads, then complete cross-sections on the way out. An easy day!

The squeezy bit of Wedgie cave is all at the start, however all three cavers navigated the passages with relative ease. Some human footholds were needed to assist with the down climb, but it was a quick entry into the cave. Continuing on through Wedgie was pretty straightforward, and not as tricky as the entrance series. We made it to A51, the final station where mop up survey was meant to commence.

Looking around the corner, we were a bit surprised… there was going passage, that kept going and going… well, maybe survey to the end could still be achieved. Eoghan and Sarah alternated setting stations while Erin sketched.

Unlike earlier sections of Wedgie, this new section had a series of parallel passages and more pillars than Erin had seen in other gypsum caves. There were areas of sandy sediment interlaced with floor/rock debris.

We continued surveying until station A70, where two leads were left on-going. One lead was a tight fissure like passage that requires crawling on one’s side. The other lead looks like the main stream passage as it continues downward, but also gets a bit tighter before bending around a corner into who knows what.

Additional leads still need to be investigated around A44, A48, A50, A53 (although this likely heads back towards a breakdown section) and A55.

No bats were noted, some white mold was scattered throughout the newly surveyed portions, but no large/organized clumps. One piece of trash was removed from the cave on the way out. No bugs were noted either. The cave is quite dusty and a mask is recommended.

Exit from A70 took Erin, Eoghan and Sarah about ah hour or an hour and ten minutes travelling at constant (but not wickedly fast) speed. Exit from the cave was made into daylight, the sun was shining and the day had turned warm enough for a late winter day.

While the goals of the day were not met, progress was made and the survey was extended.

[See below for the current map of Wedgie cave]

Investigating pits & 3B-JD cave

Jesse Adamczyk (TL), Austin McCrary, Cameron Sanchez

Executive summary

GypKaP survey of 3B-JD cave was never fully completed as there are additional passages that are not on the map. Cave should be resurveyed by small cavers.

Pit exploration

The team left the field house in the morning with the plan to drop into a few POIs and cave entrances. Prior visits to these points of interest indicated that the drops required a vertical gear, but there were no safe rigging points near the entrances of the caves. The team brought a rebar rigging kit along with webbing and ropes with the hopes that they could hammer rebar into the ground and rig off of it.

The drove in Austin’s Jeep Gladiator to an area northwest of the crossroads and drove off the main road onto a two-track. Once it was determined that the team was close enough to the points of interest, the Jeep was parked and the team hopped out. It was approximately 0.6 miles to get to the points of interest. The team travelled Eastward until they approached a barbed wire fence. Fortunately, the lowest wire on the barbed wire fence was barbless, making it easy for the team crawl under.

After about 0.5 miles of walking, the team found a dig that had been visited by Eoghan, Erin, and Minori in April 2024. The dig was a small drainage sink with a small amount of visible passage.

The team moved on for a few more minutes before finding a short vertical shaft in the ground that was about 6 feet deep. Water clearly enters the feature in large quantities as it drains from the surrounding area. In the planning from the evening before, it was thought that this was supposed to be a much deeper vertical passage that required rope to drop into. This passage was short and easily down-climbable without any rope.

Passage at the bottom of the 6 foot drop trended roughly Eastward through solid gypsum stream-cut passage. Airflow was strong enough to move small roots hanging from the walls and ceiling of the passage. About 6 feet in, the passage turns to the right and dirt sediment fills the passage to a height that makes it too tight to crawl. Due to the proximity of the dig front to the entrance of the cave and the good airflow, this cave is an excellent candidate for a dig.

The team walked back towards their starting point, under the fence, and back to the Jeep.

3B-JD cave exploration

Austin drove the Jeep for about 20 minutes until we arrived at 3B-JD cave. 3B-JD cave had been surveyed by the GypKaP project in the past, but Project Yeso cavers had yet to enter the cave due to other priorities and its vertical entrance. The goal was to enter the cave and determine if the cave matched the GypKaP survey or if it needed additional exploration and re-surveying. At only 300 feet of surveyed passage, the team was confident that exploration would not take much time. The naming of the cave was the topic of much speculation during the pre-caving activities. As expected for a group of cavers, all discussion of the meaning of 3B-JD was completely appropriate and classy. Austin parked the Jeep on a road about 200 feet away from the cave entrance. We grabbed gear and walked out to the cave.

We had planned to hammer rebar into the ground to rappel off of, but the ground was soft and sandy. Austin ran back to the Jeep and drove it close enough to the cave entrance that we could rig off of the front tow loops. Jesse grabbed a piece of webbing from the rope kit, looped it through the tow loops, and tied an overhand knot. Austin and Cameron helped chock the Jeep tires using nearby rocks.

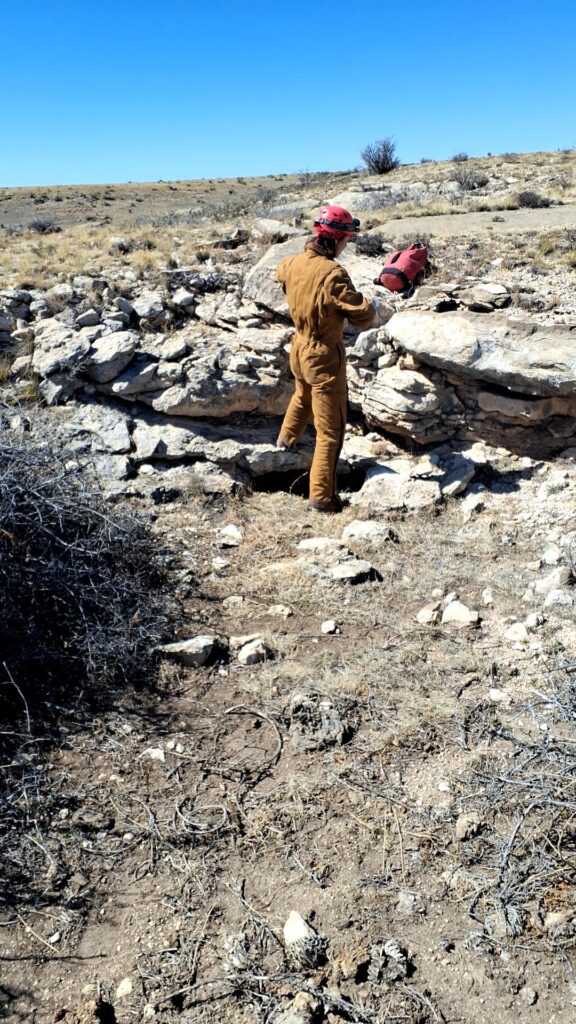

Right: Cameron just before descending into 3B-JD cave.

After gearing up and some quick safety checks, the team was off into the cave. Having rigged the rope, Jesse descended first. He went slowly and checked for snakes and loose rocks. Cameron dropped in next, descending into the hole as the snow was falling in. Austin was last and absolutely stoked due to this drop being his first vertical caving in a few years.

Once the team was all in, vertical gear was taken off and left near the entrance of the cave. The entrance was a large stream passage with several pieces of breakdown scattered about. Austin led the way downstream to passage that rapidly became crawly and difficult. He had to remove a few tumbleweeds and bushes out of the way to enter one of the crawls. As the team proceeded downstream, it became apparent that the GypKaP survey did not capture the full extent of the cave. The passage became tighter as Austin pressed forward.

After a few minutes of crawling a fork appeared. On the left was, a 6 foot tall vertical passage and on the right, a passage continuing downstream. The team recognized this fork from the GypKaP survey. The team crawled up the vertical passage one at a time. At the top of the passage there was evidence of an infeeder where the water likely entered and cut the passage. In this upper passage, the air was stagnant and the passage continued in a downstream direction. Austin led crawling downhill through the narrow passage for a few minutes. Eventually the passage got too tight to proceed and Austin decided not to push forward. Fortunately, the stopping point was in a room that was just barely large enough to turn around in, preventing the team from crawling up-hill feet first. Jesse led the way out with Cameron and Austin following. Jesse attempted to crawl down the vertical passage head first, but backed out and deemed it “a huge mistake” as it would have required hand-stand walking down a vertical tube. All members of the party crawled back down into the main passage.

Jesse led the way downstream deeper into the cave. After a few minutes of crawling, there was some narrow stream cut passage followed by a standing-sized room about 4 feet wide and 5 feet tall. This size of chamber was a bit of relief after the tight crawling.

Unfortunately, downstream from this room was even tighter. Sediment buildup left about 6 inches between the floor and the ceiling. Cameron attempted to push the squeeze but it was a bit too tight and he backed out. Jesse went in next and started moving sediment around. He used a broken piece of ceramic to dig out the sediment floor. After about 10 minutes, Jesse was able to fit through the squeeze to the other side. The passage continued to be very tight with low ceilings and rocks in the way. It was obvious that the passage kept going downstream, but Jesse turned around to help get Cameron through the squeeze. Cameron dug from above the squeeze using a flat rock and Jesse moved sediment out of the way from the downstream side.

Cameron pushed through the squeeze and made it to the other side. While Cameron was nearby, Jesse went head first deeper into the downstream passage. The passage became tighter and steeper, so Jesse moved cautiously. After a difficult few minutes moving downstream, Jesse reached a passage that was too narrow for his body to fit through. Disappointingly, he was able to see a survey station about 6 feet ahead, indicating that the previous GypKaP team had surveyed this section of passage. Jesse backed out, met up with Cameron, and they both exited the squeeze section. Austin led the way out followed by Cameron and Jesse. Being the smallest, Austin travelled through the passages gracefully while Cameron and Jesse were huffing and puffing behind. The team got back to the fork with the short vertical climb and continued moving past in the upstream direction.

Just past the fork the team arrived at a larger room and noticed that the air felt fresh. This section of the cave had a few offshoots that were not on the GypKaP survey. Cameron crawled up one of the passages and found that it kept going steeply uphill for about 50 feet until the passage turned into a fissure. The bottom part of the fissure was packed with dirt while one could see that the upper section kept going in the upstream direction. It was too narrow for any members of the party to keep progressing. Given the upstream nature of the passage, the passage is likely an infeeder that leads to the surface.

Back at the larger fresh-air room, there was a fork in the passage that was not documented in they GypKaP survey. The GypKaP survey showed an upper passage that the team had explored already, but there was also a lower passage obscured by breakdown. Austin moved a couple of blocks out of the way and was able to push into downstream passage. Cameron and Jesse waited for Austin. When Austin came back to the main room, he said “would you like to know the good news or bad news?”. Jesse asked for the bad news first. Austin said “there’s no bad news! It just keeps going!”.

The team began following Austin downstream into the passage through crawly downstream passage. It was apparent that this was actually the main passage that takes on the bulk of the water that enters this cave. The air was fresh and noticeably cool in comparison to the previously explored passages. Austin kept going forward until he arrived at a bend in some tight downstream passage. He backed out and switched places with Jesse and Cameron. Jesse with his overconfidence pushed downstream headfirst through a downward S-curve. It was a tight squeeze to get through the S-curve, but the passage opened up on the other side with just enough room to turn around. At first Jesse asked the rest of the team to come through, but they suggested they wait to see how difficult it was for Jesse to get back through the S-curve passage. Jesse explored forward for about 50 feet until he determined that it would not be wise to proceed further unless the team was closer by. He turned around and headed back towards the S-curve.

Jesse struggle-squeezed upwards through the S-curve. After several minutes, he was able to work his body around the passage so he could see Cameron on the other side. Due to his height and the tight bend in the passage, Jesse was unable to use his legs to move forward in the passage. He was now stuck and took a rest. Cameron and Austin, about 10 feet away asked “what is that thumping noise?” Jesse replied “I think it’s my heartbeat”. The team turned off their lights and remained quiet for a second. It was apparent that Jesse’s heart beat could be heard further away due to his struggle to get through the S-curve. Eventually, Jesse was able to crumple his body enough to bring his legs forward enough that he could push himself out of the upstream S-curve. Cameron and Austin were glad that they stayed back and did not go down the S-curve passage.

It was determined that the team found all possible leads in the cave and that a new survey would need to be performed to document the other passages. The team headed out of the cave, ascended the rope, and then ate some snacks back at the Jeep. Outside, the sky was sunny but the blowing wind made it cold. All of the vertical gear was de-rigged and packed up. It was only about 3:30PM, so it was decided that the team would go take a look at the Fenced Off Pit cave since none of the team members had been to that area. Austin drove the Jeep over to Fenced Off Pit where the team explored around the surface and entrance of the cave for a bit.

Due to lack of time and unfamiliarity with the rig points of the area, the team decided it would be best to head back to the field house for some bagged wine and curry.

Ridgewalking

Carrin (TL) & Evan Bowen

Expectations were high for ridgewalking this area. It was a new area for Carrin—one with interesting topography and more relief than in other parts of the gypsum plains. Andy had ridgewalked in the vicinity before, and between his assessment and lidar data for the area, it had promise. Evan just knew today was the day we would find a 90-foot pit. 🙂

We parted ways with Andy and Ethan after arranging to meet up later in the day and cruised on a two-track to a good jumping-off point. The POIs for the day were clustered in such a way that we could hit them all on foot rather than driving between them.

Devastatingly, the vaunted 90-foot pit was not to be had in this area. Thrillingly, we were able to confirm 7 POIs as not caves, redesignate one POI as a dig, and locate one pit that warrants a return visit. Even with finding no proper caves, knocking out 9 POIs felt like a huge ridgewalk!

After visiting a series of shallow limestone depressions that turned out to be closed-out collapse features not worth digging…

…we came across an area with some dig potential. In a shallow sink under a tree, we found three small holes in surface limestone, all containing green moss and blowing warm moist air, all within 20 feet of each other and likely connected underground. We spent a half-hour or so moving rocks to see if we could locate passable voids. We couldn’t—we couldn’t even get a good view inside any of the holes—but with a proper dig, anything could happen here. One hole would need a rock drill to open up a butt/hip pinch; the other two need more rock moving and shoveling of loose fill and dirt. A high-potential dig area!

During this ridgewalk, the feature that had seemingly the most potential on approach turned out to be less exciting upon examination, leading us to dub it Let Down Pit. The pit starts in limestone and breaks through to gypsum, but the potential for going passage at the base seems low given what we were able to see. We lay on our stomachs on all sides of the pit (we hadn’t brought vertical gear along) and could see all but perhaps 15 feet of the circumference of the base. Unless something miraculous happens in that small section we couldn’t see, this is a blind pit. Of course, it does need to be dropped to find out for sure. Rigging here will require rebar, as it’s not drive-up and there are no suitable rocks or vegetation nearby. Will be a fun, quick pit bounce in a scenic area, suitable for newbies/practice.

As we were winding up our POIs and approaching the rendezvous time, we saw Ethan and Andy heading our way across the rolling landscape. We walked to meet them, and so we didn’t spend the whole day above ground, we decided to hit Spider Hill Cave as a team of four before heading back to the fieldhouse (see Andy’s report below).

Andrew Orr (TL) & Ethan Haft

Saturday’s goal was ridgewalking with Ethan, focusing on checking three specific points of interest (POIs). The weather was overcast and chilly with a light breeze – perfect for hiking and exploration.

The first POI we visited was a potential cave Andrew had previously identified and wanted to examine further. Upon arrival, we found a room extending roughly 10 to 15 feet back. Unfortunately, after a thorough inspection, there was no clear indication that this room continued into an actual cave passage. We recorded our observations on the tablet and then moved on to the next location.

Our second POI required a 1–1.5-mile hike (one-way). This site was listed as a named cave in our database, but upon reaching it, we discovered that it was not a cave after all. It was just a sinkhole of breakdown. Despite this disappointment, the spot made a good place for lunch. While hiking back from this location, we carefully surveyed the surrounding terrain for any additional caves but did not find any.

After lunch, we came up with a game plan. We decided to return to our car and then head over to support Carrin and Evan with their POIs. On our way to meet them, we briefly checked a third POI but found nothing notable.

Upon regrouping with Carrin and Evan, and given the remaining daylight, we collectively agreed to revisit Spider Hill Cave—a cave we had discovered on a previous trip. Inside, we found that the passage dropped vertically quickly. Ethan, Carrin, and Andrew managed to explore approximately 50 feet of vertical descent through breakdown. At the bottom, Evan and Carrin thought that the cave appeared to continue deeper, although exploring further would require more time than we had available. Carrin and Evan encountered evidence of Turkey Vulture bones, complete with an intact skull.

After documenting our findings, we exited Spider Hill Cave and concluded the day’s activities.

Alien Crash cave

Alex Seaton (TL), Ryan Marshall, Pierson Miller

Alex, Tom Evans, and Allison Nelson had previously visited Alien Crash cave in April 2024. Due to an extremely tight constriction a little way into the cave which most of the team were unable to navigate, they had moved on to other more promising options. On this trip, the objective was to re-investigate the constriction, explore past it, and potentially begin a survey of the cave.

After driving out from the field house, getting changed, and hiking out to the cave, we arrived at around 11:15am. It was cold and windy, and there were light snow flurries, so we hurried on into the cave.

From the entrance sink, the entrance is a tight horizontal tube that goes for around 10ft before reaching a drop of around 12ft that is easily free-climbed. From the bottom of the climb, the cave continues but begins to get very tight. This is where the constriction is that stopped the previous team. The passage has two right angle bends, one to the right, and one to the left, such that the passage afterwards continues in the same direction as before, but shifted a couple of feet to the right. On the previous trip, Alex had been able to get through the constriction but briefly got stuck on the return journey before managing to make it through.

Our first job was to scope out the situation, so Ryan and Pierson made their way in and took turns to investigate. Both made a valiant effort but were unable to get through. After a while trying different maneuvers both got tired and we decided to stop for lunch. Out on the surface the weather had improved somewhat.

After lunch, we assessed the constriction again. Ryan gave it another go, but was still not able to make it through. Additionally, looking at the parts of the passage that were preventing him from making progress it seemed like it would take a significant amount of work to enlarge it to the point where he’d fit. We decided it would be best to send Alex ahead briefly to see what lay ahead in the cave before working on it further.

Alex headed on through the constriction. The cave opens up immediately into a small chamber 15-20ft in diameter and with room to stand. The downstream continuation passage heads back from the chamber, almost directly underneath the squeeze. Alex had poked his head inside this in April the previous year, but had turned around. Continuing on, the passage ceiling gradually dipped from a comfortable hands-and-knees crawl down to a flat-out crawl. After around a body length, it further narrowed to the point where Alex was unable to fit through. This was frustrating as the passage appeared to open up after a couple of feet, and obviously continued on.

After Alex made his way back to the rest of the team, we decided that given we’d just need to dig another constriction, it was not worth pursuing this cave further. By this point in the day we didn’t have time to work on our backup option of Tummy Troubles survey. Instead, we decided to do some ridgewalking before heading back to the field house.

We visited two locations near Tummy Troubles which Alex had spotted in the lidar, and could potentially feed into Tummy Troubles. The first was a small drainage sink, which drops into a tight pit around 10-15ft deep. We didn’t attempt to climb down since we’d already changed out of our caving gear, but it would be worth further investigation on a future trip.

The second location was less promising. It looked like it might take water, but this appears to drain slowly into a depression filled with sediment. On the plus side, we found an old pot embedded in it.

Having investigated these, we decided to finish up for the day and headed back to the field house.

Sunday 9th March

Wedgie cave survey

Erin Vair-Grilley (TL), Eoghan, Ryan Marshall

Today Erin, Ryan, and Eoghan went back to Wedgie Cave through the dusty crawl again — god f****** knows what we were inhaling — we were to push the branch from station A33 and survey what we found.

Well, just like the previous day we failed to “kill the cave”: Wedgie Cave now has a B survey too. We had a great time (in hindsight); the beginning of the B survey is exceptionally dusty and has a lot of loose soil on top of large gravel. The branch that veered off of the A survey was of interest to us because when the survey centreline is put into QGIS and plotted on top of satellite imagery and the POI layer, it trends along a large surface collapse. Ultimately we didn’t come across any signs of access to the surface in the vicinity of the collapse.

The B survey continued past the area of the surface feature. It trended Southwards and climbed about 10 feet towards the surface. The passage then formed into a narrow fissure which continues for at least 45 feet. Presently, the head of the push is at a particularly narrow part of the fissure where the caver is sandwiched between the wall on one side and a flake of gypsum — no caver has squeezed beyond the flake. First Ryan tried, then Erin, then Eoghan. We all decided that it was either too tight, or too close to the end of the day.

Tummy Troubles survey

Alex Seaton (TL), Austin McCrary, Pierson Miller

Our team’s objective for Sunday was to continue work on the sketch in Tummy Troubles. With the usual sleep deprivation exacerbated by the time change the night before, we were definitely a little worse for wear, but fortunately did not need to travel far into Tummy Troubles for this trip.

After getting changed and heading to the spot we’d be surveying, we got the survey gear out and got to work. This time, Austin was the volunteer/victim who’d be learning to sketch. Alex gave him a quick tutorial to introduce him to Topodroid, and then he got started. Topodroid has a pretty steep learning curve, but Austin was game and made a valiant effort.

While Austin worked on the sketch, Pierson worked on pushing some side leads. He first investigated a lead heading west from A18, which was a little way ahead of where we were sketching (A15). He was able to push it for a short distance, but it got very tight and he had to turn around.

We took a quick break for lunch and then continued working. After the break Pierson worked on opening up the small passage that leads off from the bottom of the aven at A14. This was blocked by a large rock, though on previous trips we’d noticed that there was going passage past it. Fortunately Pierson was able to shift the rock out of the way and access the passage behind it, which surprise-surprise turned out to be very tight (but nonetheless appears to go).

Meanwhile Austin was making good progress with the sketch. He worked through to A16 and was able to connect the sketch with the B-survey sketch, despite feeling increasingly nauseous. Given Austin’s condition and the fact that we were getting close to the out time, we decided to call it a day.

Before leaving, we had to extract Pierson from the lead, which turned out to be challenging. He had gone in head first down a steep slope, which was a difficult manoeuvre to do in reverse. But he managed it!

We’ve still got plenty of work to do on the Tummy Troubles survey, but it’s heading in the right direction!

Ridgewalking (western area)

Carrin (TL), Sarah Haft, Ethan Haft

What a pleasant day of ridgewalking! And a good introduction to ridgewalking the gypsum plains for new cavers and new-to-Project-Yeso Ethan and Sarah. The day’s target area contained multiple POIs and was largely flat, gently sloping, and easily walkable.

Upon arrival, we were greeted by four friendly horses. They hung with us for much of the day, and as we left the field, they stuck their heads in our open car windows to say goodbye. Sweet!

The first several POIs we checked turned out to be large dolines, 70–200 feet wide, with a bit of breakdown here and there but no going leads. The flatness of the landscape here and the lack of obvious drainage didn’t bode well. We also found a small solution collapse that was frustratingly closed out.

We finally had some success when we came to an unassuming limestone ledge with a hole at its base. Ethan and Carrin poked around the hole, and Carrin slithered in to discover a spacious slab chamber with a small lead… that opened into canyon-style limestone passage ~20 feet high! This was the most exciting find of the day and certainly warrants survey. Anything could happen beyond where Carrin turned around for time, but the passage dimensions and joint control make this feel like a promising lead. We held off on naming this cave until more folks can go in and get a feel for its character.

Our other big find of the day was described in QField as a “large depression with rock shelf on southern side that could be hiding a cave.” It was not, but a rock shelf on the northern side of the depression was! Ethan and Carrin popped into a stoop-walking entrance under an overhang and emerged into a large chamber, some 40 feet in diameter with an 18-foot ceiling. It held some interesting mammal bones but no leads. The ease of movement in the chamber and a generally hospitable feel led us to name this place Mescalero Chamber.

Ethan and Sarah took turns operating QField throughout the day. Their assessment was that the platform was every bit as good as other GIS software and better than some. (Kudos to Alex!) Their background in geology fieldwork made the tablet and the purpose/method of ridgewalking a snap for them. Glad to have them on board with the project, and looking forward to a return trip to this area!

Ridgewalking (eastern area)

Andrew Orr (TL), Evan Bowen, Cameron Sanchez

Sunday’s main goal was to sample mold growth within Sparks-Zalea Cave. Given the unusual nature of the mold, precautions were taken—Andrew double-masked, while Evan and Cameron opted for triple masks for additional safety. Upon entering the cave, we went directly to the mold growths, some of which exhibited dendritic patterns across the rock surfaces. After carefully collecting the samples, we exited the cave.

Following the mold sampling, we shifted to ridgewalking and soon discovered a promising cave fed by a large drainage. Evan and Andrew explored inside, while Cameron conducted a thorough search of the surface area for additional openings. Inside the cave, we traversed approximately 400-500 feet of passage, initially following a water channel that cut into a large room measuring about 35 feet tall by 30 feet wide.

Numerous smaller side passages were noted but not fully explored. At the bottom of the large room, the passage narrowed into a crawl space before leading into a tight pit beneath breakdown. The pit, estimated to be 20 feet deep, appeared climbable but was narrow and difficult, possibly requiring rigging on boulders or a handline. Beetles were observed within the cave as well.

After documenting this cave, we proceeded to investigate one final POI located approximately half a mile from the road. However, upon reaching it, we determined it held no significance.

With the day’s objectives successfully completed, we returned to the vehicles and headed to meet up with the other teams.